Equity Efforts Need More Social Science, Not Less

The growing trend of referring to methods of social science as intellectual tools of the oppressor disempowers the disadvantaged and acts as a hindrance to improving opportunity.

I Didn’t Want to Do This, But…

I didn't really want my first “real” post to be about race and social justice because it feels so cliché and stereotypical, “Of course the Black guy is going to write about these things. Isn’t that what all Black academics do?” (No! But also, kind of).

But I can promise you two things.

First, this won’t be a typical “We must defend all racial justice efforts at all costs” piece.

Second, if you can just stick with me through a month or so of this, I promise I’ll get to some other interesting topics like parenting, schooling, relationships, and so on. And my aim is to make most of this publication about those things. I just need to get some things off my chest over the next few posts. Just think of it as an early Black History Month thing.

The Master’s Tools

Not too long ago, I commented on an acquaintance’s post about equity and justice in schools. He expressed his concerns about education advocates beginning to drop the use of “equity” (presumably in anticipation of the Trump administration) and how the equity term doesn’t go far enough. Justice is the term that really gets to the heart of what we’re after, he argued. I responded:

I think equity and justice suffer from the same definitional problems. How do you know it when you see it? The answer can't be equal outcomes. If it's equal opportunity, what dimensions of opportunity and what does that look like? I'd like to see more work among those in this space on clarifying what is meant and how we can determine progress toward the goal.

My point was that to advance something like equity and justice in schools, those concepts need to be well-defined, and we need ways of assessing progress toward those goals. Otherwise, how will one know when it has been achieved? Even if you believe that equity is a journey and not a destination, how do you know whether the journey is progressing, stalling, or reversing?

Basically, I was arguing for applying more social science methods to questions about equity and justice in schools.

“Stop using the master’s tools as your definition,” a commenter wrote back.

I didn’t know this person and wasn’t exactly sure what they meant by that, but I was familiar with this term, which originates from the Black feminist Audre Lourde’s 1979 speech, “The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House.” A quote from that speech:

For the master’s tool will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.

Lorde claims in that speech that feminism has problems with racism, homophobia, and classism that have gone underacknowledged for far too long. The “divide and conquer” approach of these forms of bigotry was endemic in feminism and was a strategy commonly used by oppressors (the master’s tools), she argued. And these tools can only serve people like oppressors; they can’t benefit marginalized people, at least not in any ethical or meaningful long-term sense.

This is reasonable. While becoming exclusive feminists may benefit those doing the excluding, it would become an amoral movement, ultimately resulting in its demise. But reasonable is not a way to describe the current public discourse which drastically overextends Lordes’s analogy. In far too many circles, oppression is synonymous with Whiteness, with Whiteness primarily consisting of a litany of trite stereotypes. Further, these stereotypes include principles, viewpoints, and other ideas that are considered White ways of thinking and being that differ from how non-Whites behave.

Overextending the Metaphor

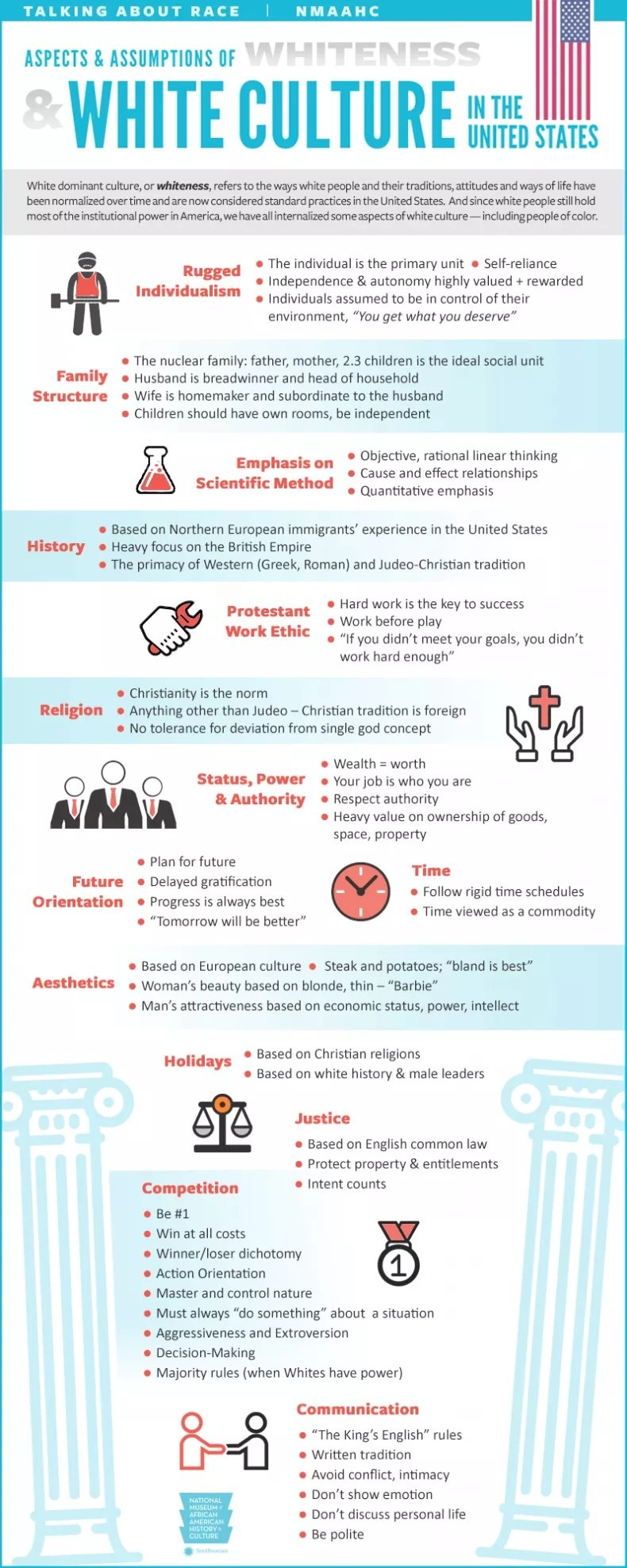

Take this classic example. In 2020, the Smithsonian’s American Museum of African American History and Culture posted a visual defining “Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness and White Culture in the United States”. According to the document, one “aspect of White culture” is scientific thinking and the scientific method, which includes “objective, rational linear thinking,” “cause and effect relationships,” and “quantitative emphasis.” I remember thinking that this had to be satire or fake news when I saw it. Unfortunately, it was real, and the Smithsonian eventually removed it from its site after being lambasted by critics.

But even more unfortunate was that this visual was tapping a very real and growing sentiment, especially in some social justice circles, of scientific methods and thinking as the purview of Whites, not Blacks. I’ve observed it several times in the social sciences, where the trend is concentrated in education, sociology, social work, and psychology. Thankfully, this view is not ubiquitous, as excellent scientific work is being done on opportunity and equity. Raj Chetty’s Opportunity Insights project at Harvard, Sean Reardon’s Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford, and Roland Fryer’s work at Harvard are a few examples of top-level social scientific work being done in this area.

But I worry about the deep and unjustified cynicism toward scientific methods that has been increasing in the social sciences, especially among those identifying as scholar-activists. For example, while presenting on a panel at a conference, during the Q&A session, a White woman in the audience expressed her concerns about our exclusive use of scientific methods to address the issues of school assessment among diverse populations. And as she was speaking, a few Black audience members co-signed by nodding their heads and vocally agreeing. “Interesting”, I thought—cross-racial agreement on scientific methods being inadequate for the marginalized. My experience has been that it’s not uncommon for Black and non-Black (especially Whites) social justice advocates to agree on this view.

Many things don’t add up about this way of thinking.

For one, why can’t the intellectual tools used by the oppressor be useful for freeing the oppressed and achieving justice? Slave owners denied reading and other forms of education to enslaved people exactly because they knew the danger of those tools being turned back upon them. And how is it that tools become “theirs” because “they” value and use them now, and one of the many historical uses of them was to oppress others? Do the tools become perpetually contaminated by some bad people within a dominant group who use or abuse them?

Imagine if this was how the world worked—where, because a hammer has been used for oppressive purposes by a group of people for a long time, it has no value to people who want to build homes for the homeless. These people who want to work for progress should forever surrender hammers to those who use them for oppressive purposes. This sounds more like superstition than reality. But this is how social scientific methods are sometimes treated in some social justice circles. What concerns me the most about this mode of thinking is how quickly many historically marginalized people are to disempower ourselves by turning over useful intellectual tools to the very ones we blame for our oppression. Worse yet, this act of surrender is presented and celebrated as empowerment, further disenfranchising the people who need the tools most.

Tools of the Marginalized?

So, if critical thinking, reasoning, and science are the tools of the master, what are the tools of the oppressed and marginalized? I’ve asked variations of this question several times over the past few years and have yet to find a persuasive answer. Many of these proposed solutions involve dismantling or abolishing something—usually systems. That is, they argue certain institutions are so fundamentally flawed that we need to radically restructure them by… That’s where things get very hazy.

Usually, there is mention of reimagining (this word is used a lot) or dreaming up something better, but the details are light, and any evidence offered to support the argument is even lighter. A few times, I’ve heard that the use of qualitative data methods is the alternative to science, which makes little sense because this still employs the systematic approaches of the scientific method, just with a different type of data and a different set of analytic techniques.

The use of storytelling is another commonly proposed alternative to science. This truly is a non-scientific approach and is a powerful way to convey perspective and experience with depth. But is it better for decerning the nature of social problems and what to do about them than scientific methods? Wouldn’t the greater likelihood of storytelling reflecting biased views make it especially useful to oppressors since oppressors often have greater influence over public narratives?

Versions of what some call critical social justice have also been offered as alternatives to social science, such as critical race theory, decolonial theory, antiracism, critical feminist theory, and others. Again, these are non-scientific approaches, but the question remains whether they serve the historically marginalized better than social scientific methods. And more importantly, how would we know? Most of these approaches begin with very strong assumptions that are exempted from skepticism and inquiry, such as racism being ever-present and the primary, if not only, driver of racial disparities. These assumptions are treated as absolute and obvious truths that you are to never question, as doing so demonstrates your cluelessness, naïveté, or bigotry.

The problem is that all of the alternative approaches to social science mentioned above actually introduce more bias than they mitigate, either by using approaches that increase subjectivity (storytelling) or by starting with strong assumptions about social phenomena (critical social justice approaches). I suspect a large part of this is motivated by intentions to bend science to fit social justice narratives rather than using science to honestly understand and address social justice-related issues.

While social scientific methods are far from perfect and are by no means devoid of bias, at least one of their main goals is to reduce bias from observations and analyses so we can see things as they are rather than what we want to see. For example, one of the reasons the double-blind randomized controlled trial is considered a gold standard is because of its power to address biases of the researchers and study participants. Conversely, the approaches above communicate reality in ways that are deeply dependent upon the views, assumptions, and desires of the observer.

Why So Critical?

For some of you, this critique likely raises questions. Why am I so critical of these ideas, many of which are developed or advocated for by people of color like me? And why now, right at the start of a new administration that vows to eradicate all forms of DEI? Is it a “grift”? Have I been brainwashed by The Man? Am I doing it to curry favor with those who would oppress me? Am I just stirring the pot?

No.

I’m critical because, at the end of the day, if one really cares about understanding and addressing complex social problems, one should care about what ideas get the job done the best. This requires being skeptical and critical across the board, not only of the side that feels less resonant to you. That side can be wrong, too. For the sake of fairness and anything else we want to improve, we need to be a lot harder on ideas. Ideas need to exist in a brutal survival-of-the-fittest environment. People should be safe, but ideas should always be under assault. That’s how we discard the bad ones and identify the best ones that produce progress. The problem is that we have been exceedingly critical of “traditional” ideas and have largely exempted many of the newer social justice ideas from such critique. They need to get that smoke, too. And not just from outsiders but insiders as well. So, continue going hard on traditional social science, but bring that same energy to proposed alternatives.

I’m in no way dismissing the importance of work on equity and social justice. On the contrary, it’s because I believe concepts of fairness and opportunity to be so important that I think they deserve more serious engagement and inquiry. How else can we get others to take us seriously if we reject the use of powerful and reliable intellectual tools for understanding and advancing fairness? More importantly, how do we reliably and sustainably move towards and achieve fairness without such tools? This needs to involve more than sharing the personal stories, views, and experiences of the marginalized. We should expect more of ourselves, such that we allow for the possibility of being wrong and biased and use the best tools for handling this.

Notes: For a related argument to points made here, you can see my in-press piece, Universalism is Not White. Also, in the future, I’ll try to keep these posts shorter!

Tremendous read. I am avidly seeking understanding why it is so acceptable for many people I’ve worked with or dated to treat me with contempt because I’m white. It’s heartbreaking because these same people have also showed me respect and caring and we’ve naturally connected in so many ways. But over time as we get to know each other, instead of feeling like there’s mutual support and understanding like there would be in a healthy co-regulated symbiotic relationship, clear signals are shown that I am not deserving of sympathy or empathy when I struggle because I’m “privileged.”

On my side, I want to be and make the effort to be there for people I care about and I never measure their worthiness to receive my energy based on any external characteristic they possess, but more on how I value our relationship and how special I see them as an individual.

This article helped me find clarity in where their justification for seeing me/treating me as “deserving less” comes from. The belief that certain basic ideals like “delayed gratification” or “planning for the future” extend out to “if my white friend experiences disappointment over failing at a “white” value or happiness over succeeding at a “white” value I (as the “oppressed” not only can’t connect with that, I should turn away from it with indifference or even disgust. That is why contempt is the result.

This is an example of how racial tensions rise one degree at a time. We are all in racially diverse environments trying to work together, get to know one another, building communities and families. But our trust is only going so far. If I am offending you by “being myself” and you are responding in a way you think is appropriate because you’re offended but I don’t see myself as offensive because I’m genuinely just trying to connect, we have a big problem.

I’d love to read what you have to say about how to repair this connection and heal our misunderstandings of each other, as well as how to show people who identify more with group identity that being seen and valued as an individual better serves them.

I prefer the yin/yang view of the world in which every system contains the seeds of its own demise. This is the opposite of Audre Lourde‘s claim about the master’s tools.

More importantly, I define equity in my book, Schooling for Holistic Equity, with reference to the satisfaction of primary needs, where needs are defined scientifically. Oppression must be experienced in order to exist. If a person is experiencing well-being then that is the opposite of oppression. My expertise is in psychology, so my main focus is on the psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence. Those are measurable, so we have the capability for objectively assessing the status of someone’s oppression.

Here’s a relevant link to my site: https://www.holisticequity.org/equity-in-schools.html